We live in an age of symbols. An age where the representation of a thing has more value than the thing itself. Where the brand itself is valued over the branded product. We imbue brands with properties and feelings, which can be set through advertising. The brand is eternal, unsullied by the failings of the real. So it has overpowered the real to become our dominant way of relating to our existence.

Symbols can provide useful shorthand representations. Mental shortcuts save us the time of evaluating each thing separately. But with the advent of mass media, advertisers learned an important lesson. Our relationships with symbols are distinct from our relationships with what they signify.

Our perspectives on products are affected by how they perform when we use them. But the brand remains untarnished. Tens, hundreds, or even thousands of lackluster McDonalds hamburgers won’t erase the nostalgic longing for a Happy Meal. That particular burger was unsatisfying, not the McDonalds brand. The Nike swoosh still signifies fitness and athleticism, even if most users never traipse past the shopping mall. The brand can never fail the customer, because the brand does not exist.

The brand is merely our mental shorthand for the product. But this shorthand is warped and twisted by the advertising we soak in every day.

We imbue brands with properties and feelings. We lust for them, put our faith in them and defend their honour. We are nostalgic for them, for the comforting embrace of a box of Arnott’s Shapes bringing us back to Saturday morning cartoons. These perspectives are only tenuously informed by reality. Instead, they have been consciously built through decades of advertising.

But we have soaked in advertising for so long that the symbols have taken on a life of their own. No longer do they merely signify products. Our connection to brands is so strong that we seek out the brand itself rather than the product it once signified.

Red Bull no longer has any connection to the real caffeinated energy drink. Red Bull is now a network of sporting teams and events ranging from a Formula 1 team to the X-Alps paragliding contest. The mental shorthand has been completely perverted. Red Bull stands for challenging the limits of man and machine – just the kind of thing which an overworked office drone needs to get them through the day. Their engagement with the brand just happens to take the form of a nasty metallic drink.

Brands are mass, shared delusions. Because advertising is so unrelenting in the mass society, all our mental shorthands are similarly perverted. Your idea of the Apple brand is basically the same as mine. We even choose to adorn ourselves with brands to appropriate a fraction of their imputed qualities for ourselves.

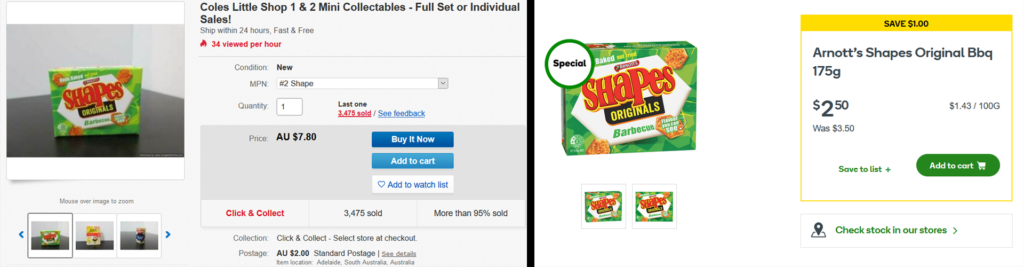

The apotheosis of this comes in the Coles Little Shop promotion. Shoppers can, by spending enough money, collect little tchotchkes. This is not remakable, in itself. But these tchotchkes are not tie-ins to popular media. They are not even representations of the products sold. They are representations of the branding of the products.

One can collect (and many do), little symbolic representations of the packaging of products sold at Coles. This is the brand made manifest, shorn of any connection to the product itself. There are no biscuits in a Little Shop representation of the Arnott’s Shapes brand. Perhaps unsurprisingly given the depths of our connection to brands, these have proven so popular that they are often onsold for more than the actual products.

They offer the imputed qualities of the brand without the risk of the real product. A Little Shop representation of Arnott’s Shapes offers the comforting nostalgia without the empty calories. The Red Bull idea of a brand made manifest, without the hassle or cost of churning out litres of nasty energy drink. Any chance of the product devaluing the brand has been removed.

The real is messy, complex and often disappointing. The brand is not. The brand has ascended to primacy over the real. But the brand does not exist.